Storytelling: Why the Brain loves Stories

Last updated on November 21, 2021 at 17:03 PM.Storytelling is an art. An art with many secrets. After all, who knows exactly what captivates, excites and makes the reader laugh or cry. Every storyteller has wrestled with this dilemma: how do I tell it to the reader (and therefore the potential client)?

Introduction

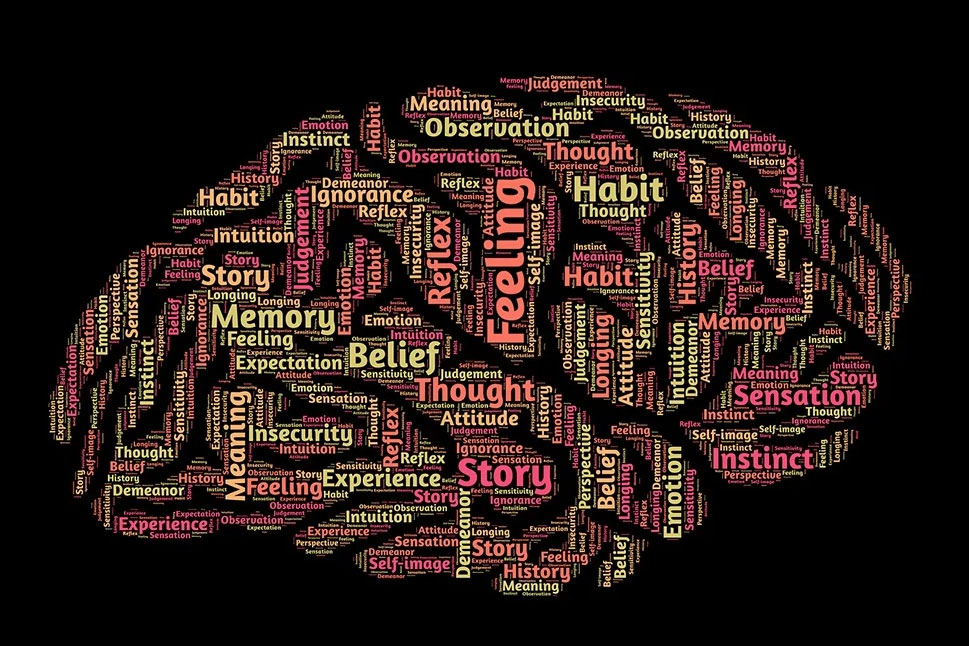

What has been known for some time however is that storytelling is a gateway into the minds of your clients because it helps to embed the message deep into their little grey cells.

With the aid of neuroscience we can go one step further now and reveal the secrets of successful storytelling. Or to be specific, by looking at monkeys neuroscientists have discovered how the brain perceives and experiences stories and we can utilize this knowledge for expert storytelling.

Our tale begins with a journey in time back to the Italian city of Parma (sadly, not to gorge on the famous ham ….). It is the year 1991 and the Italian prison doctor and part-time scientist Vittorio Gallese has just accidentally discovered the so called mirror neurons in monkey brains. Gallese has found that the neurons in monkey brains that are responsible for grabbing objects fire even if the monkey in question merely observes another ape reaching for an object. In other words, simple observations already trigger the impulse to grab something. Of course other areas of the brain are also involved in this process since apes and humans are equally capable of suppressing such impulses.

In terms of human beings this plays out as follows: mirror neurons respond to visual cues (e.g. facial expressions) and ensure that we can empathise with the emotions of others. If, for example, we see somebody who is visibly angry these neurons trigger feelings of anger in us also. This way, we can better understand the intentions and actions of others because we basically simulate them (“As If” actions). This also explains the notion of laughter being regarded as “infectious”.

Eat the chocolate!

“Whether I feel disgust myself or whether I see a disgusted face – it’s all the same for these cells”, says the German-French psychologist and brain scientist Christian Keysers. “When you take a piece of chocolate and eat it a certain network of brain cells is activated – let’s call it the ‘Eating-The-Chocolate-Network’. The sight of people, who eat chocolate, triggers an emotion in us that tells us what it would be like to do the same.”

The activities of these very talented brain cells are constantly present in everyday life. For example, you sit on a park bench relaxing while watching children play. One of the kids falls over and starts to cry. Who wouldn’t want to immediately get his hanky out and console the poor thing? You feel the pain of the child despite the fact that it wasn’t you who fell over, which is the activity of your mirror neurons.

Let’s look at another example: you snuggle up in a cosy cinema seat with your popcorn and enjoy Ingrid Bergmann and Humphrey Bogart in “Casablanca”. Suddenly, the illustrious words “Here’s Looking At You, Kid!” echo through the dark cinema and you start to well up. Why? The fact that Ingrid Bergmann is crying when she realizes that there will be no happy ending is understandable but your life won’t be affected by this at all. And yet, you feel the emotions of Ingrid Bergmann. The German news magazine Der Spiegel summarized this very poignantly as “The Might of Compassion”.

Keysers explains the mechanisms of this “might” as follows: “Empathy is deeply embedded in the architecture of our brains. Things that happen to others have an effect on almost all regions of our brains as well. We are designed to behave empathically, to search for the connection to others.”

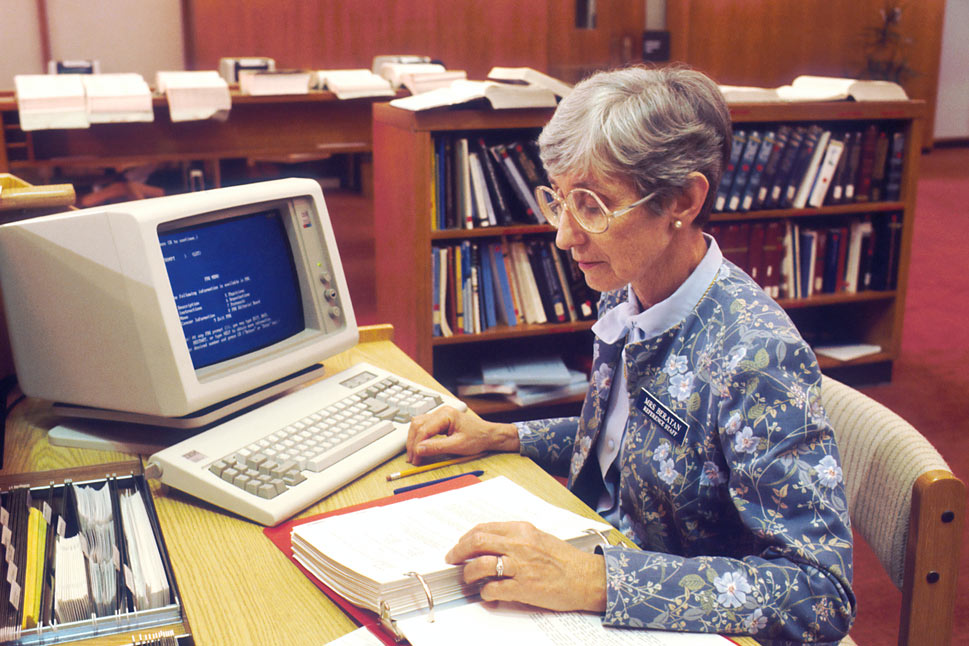

How to make the mirror neurons tingle

This begs the questions how a writer can use the activities of these miraculous mirror cells and trigger this emotion called empathy, which is so deeply embedded in our brains? Again, we turn to science for the answer: shortly after Gallese discovered the mirror neurons in monkeys they were found in human beings as well – in the so called Broca and Wernicke areas, which are part of the language center of the brain. In other words: the human speech center is very well equipped to “empathize” and this mechanism can be activated through language.

There is a good reason why new reporters are sent to the heart of the action because they can describe best what they have seen with their own eyes. Although the famous headline of the German tabloid Bild “Bild was there first to interview the corpse” has an ironic twist it nevertheless illustrates what makes people journalism (and many other forms of journalism) tick – the journalist has to be on the spot as close as possible to engage his own mirror neurons with lightning speed and consequently trigger the reader’s mirror neurons through his reporting.

And it is exactly for this reason that stories of novelists who describe their own experiences are particularly exciting, thrilling and authentic. Anyone who has ever read Hemingway’s account of a bull fight knows what I am talking about. Such stories directly address our mirror neurons, which in turn replicate the emotions of the author.

This means that there is a scientific explanation for the effectiveness of good storytelling. Human beings are wired to almost witness first hand a story well told. They even crave it because the brain loves an engaging tale. The rule of thumb for successful writing is to be able to “feel” your own story and put this emotion in words that trigger exactly those emotions in anyone, who reads the story. If you can “feel” your own story you can be sure that your reader can do it too. The litmus test is to read it yourself first and observe your emotions: are you curious, excited, interested and thrilled? If the answers is yes then you have scored because now you know that the reader’s mirror neurons will create what Keysers called “the almost mythical feeling of connectedness” and you can assume that your message has been deeply embedded in their brains.

Gerrit Grunert

Gerrit Grunert

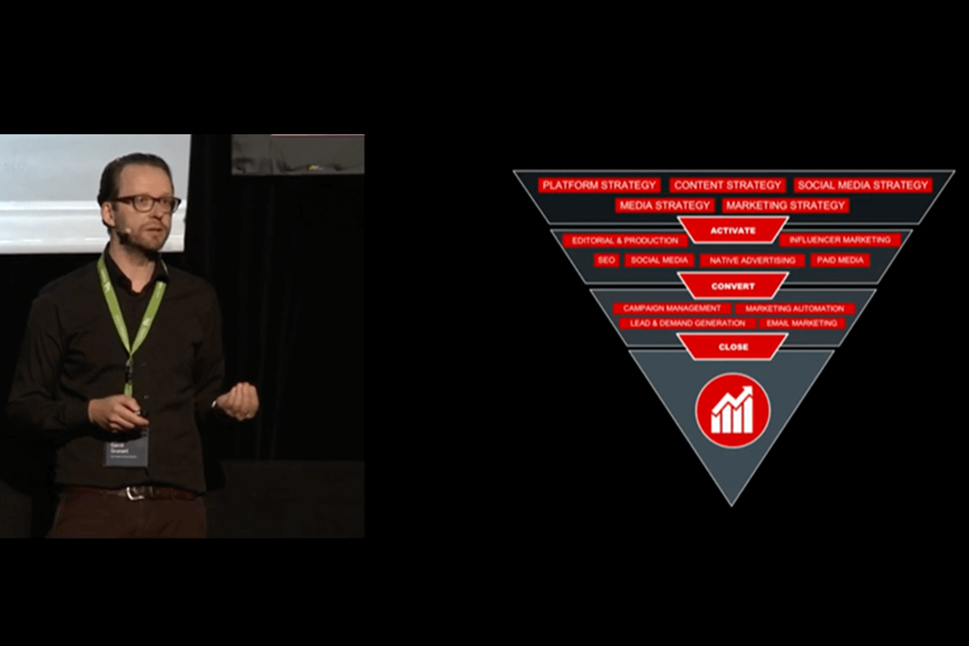

Gerrit Grunert is the founder and CEO of Crispy Content®. In 2019, he published his book "Methodical Content Marketing" published by Springer Gabler, as well as the series of online courses "Making Content." In his free time, Gerrit is a passionate guitar collector, likes reading books by Stefan Zweig, and listening to music from the day before yesterday.